What if Moses had taken a page out of Isaac’s playbook and had blessed Pharaoh?

Shabbat Bo 2021/5781

Rabbi Stephen Weiss

B’nai Jeshurun Congregation

There is one very dramatic moment that takes place on the night that the Israelites left Egypt.

Pharaoh arose in the middle of the night, he and all his servants, and all the people of Egypt, and there was a great outcry throughout the land of Egypt, a shriek, a scream filled the land, for there was not a single house in all the land of Egypt in which there was not a first born who died.

And Pharaoh went to Moses and Aaron in the middle of the night, and he said: ‘Get up and leave from among my people – you, and the Israelites, and go worship the Lord as you have spoken. Take your flocks and your cattle and go, as you have spoken, that is, on your terms.”

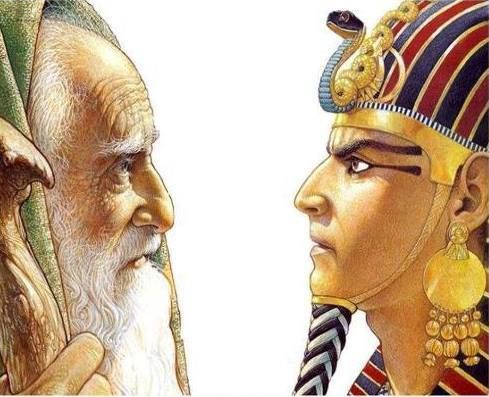

This is the moment of Pharaoh’s complete surrender to Moses. After many months of negotiation, and after ten plagues which have struck the possessions, and then the bodies, and then the lives of the Egyptian people, Pharaoh is ready to cry uncle.

“Enough!” he says. Kumu tz’u mitoch ami! Get up and get out from the midst of my people. Go away! And take your people and your flocks and herds and go worship Adonai as you have demanded.

And then Pharaoh adds three more words to his statement of surrender: He says to Moses: uveyrachtem gam oti — “And bless me too.”

Pharaoh’s will is broken by his grief over his son dying, and he is now ready to do anything to bring this suffering to an end. Once a great and mighty ruler of an empire who was worshipped as a God, Pharaoh has been transformed into a broken man, a bereaved father. The pain is more than he can take. He will accede to anything if only the plagues would stop. He is in need of comfort. He is in need of hope. He is in need of blessing. Even if that blessing will come from the one that up until now he has viewed as his adversary.

And Moses? What does Moses say in response to this request? Nothing. Not a word. Or if he did say something, the Torah does not record it. The text moves on to describing the Egyptian people urging the Israelites to leave.

It seems Moses just turned and walked away. And who could blame him? After being betrayed by Pharaoh’s father when he was forced to flee from Egypt? After having witnessed the suffering if his people and Pharaoh’s hateful intransigence? Who could blame Moses for walking away and not blessing Pharaoh?

But what would have happened if Moses had found it in his heart to bless his adversary in that moment?

We might learn an answer from another time in the Torah where a person who is upset that he feels he has lost asks for a blessing. That is Esau. After Jacob has tricked his father into giving him the blessing of the first born, Esau returns from the hunt with the game he had captured for his father’s meal. Esau learns of Jacob’s trickery. He knows that once a blessing is given it cannot be taken back. But in his anger and sense of loss, he cries out to Isaac, Habracha achat hi licha, avi, barchayni gam ani — “Do you only have one blessing, my father? Bless me too!”

And what does Isaac do? Isaac gives his son, Esau, a blessing. It is a substitute blessing. It is not as special as The blessing that Isaac gave Jacob, it is not the blessing of the first born with its promise of inheriting family leadership and covenant, but it is a blessing nonetheless.

Isaac understands that Esau is hurting and angry, that he feels he has been cheated by his brother and rejected by his father. He offers a new blessing to him in order to reassure him that he is not rejected, and to comfort him by letting him know that Jacob’s future success will not come at Esau’s expense. Jacob too can receive God’s blessing and not only survive but thrive. It is way of telling Esau that this is not a zero-sum game. Both Jacob and Esau can have a good future.

Perhaps this is why Esau never makes good on his threat to harm his brother. He certainly could have. By the time Jacob is heading back to Canaan, Esau has become wealthy. He has many servants and flocks. Indeed Jacob knows how powerful his brother has become. That’s what he divides his camp and separates himself from them, to protect his family should Esau attack. That is also why Jacob sends Esau gifts in advance of their meeting. But maybe despite Jacob’s fears, his father blessed Esau placated Esau’s anger since that blessing had been realized in Esau’s prosperity, Esau had no desire to harm him.

If we read the midrash, these two stories – of Esau and Pharaoh asking for blessing – are more similar than they at first appear. Remember that this Pharaoh grew up in the palace with Moses as his adopted brother. Surely just as in any home the addition of a second child created sibling rivalry. But the Midrash Ha-Gadol says it went farther than that. It says that the father Pharaoh would hug and kiss Moses while the father Pharaoh’s son would look on. Baby Moses would also pick up the crown, play with it, place it on his own head and playfully throw it on the floor.

And Pharaoh’s older child by birth, the one who was destined for the throne, would watch this and would tremble with anxiety. He would wonder “Is my adopted brother going to destroy my dynasty? Is this new child going to displace me?” Just as Esau feared that Jacob’s blessing would be his own downfall. So too Pharaoh feared that Moses would end Pharaoh’s dynasty. The death of his first born must have felt like a confirmation of those fears. So he, like Esau before him, pleads, “bless me too.”

What if… What if Moses had taken a page out of Isaac’s playbook and had blessed Pharaoh? What if he recognized Pharaoh’s pain and fears even in the moment that he had defeated him and sought to comfort Pharaoh and offer him hope for the future? Might things have turned out different? Perhaps having been blessed, Pharaoh would not have boiled over again with feelings of anger, resentment and loss after relinquishing control of the Israelites. Perhaps he would not have sent his army after them to recapture them, causing the drowning of his chariot forces in the sea.

We will never know. But that question, “what if…?” remains with us. What if whenever we found ourselves in conflict with another, whether in politics, at work, with our friends or in our family, we found a way to bless our adversary in their moment of defeat, to reassure them that they still matter, that they can still flourish, that we can find a way to both share in a better destiny?

Yechezkel Landau, a peace activist in Israel, wrote a poem in the heat of one of the recent past wars with Hamas. He wrote:

What if our compassion and our empathy were as strong as our capacity for self-justification and self defense?

What if both of us—we and they – could see ourselves as interdependent, rather than as isolated and threatened by each other?

What if both of us—we and they – could see the Image of God in ourselves and in each other, rather than they seeing us as hostile invaders, and we seeing them as Nazis incarnate?

What if education towards peace could be a part of the curriculum in their schools and in ours?

What if their media and ours conveyed humanizing images of each other instead of reinforcing our prejudices against each other?

What if they saw us as a people coming home, and we saw them as a people displaced and dispossessed?

What if they could understand and acknowledge the existential fears of the Jewish people after the Holocaust, and after so many wars and so many acts of terrorism? And what if we could understand and acknowledge the existential fears and shame and pain and anger that they feel after so many defeats?

What if we and they could see our problems as joint problems, such as lack of water and increased poverty, and despair, and extremism, and not see our relationship as a bilateral conflict between them and us?

What if our children learned more Arabic, and theirs learned more Hebrew, so that we could literally understand each other?

What if we and they could imagine what a genuine peace without a winner and without a loser would look like?

What if? What if? What if?”

You do not have to agree with everything Yehezkel landau says in this poem. I do not agree with all of it. The truth is there are hardly any doves left in Israel because realities on the ground have crushed our dreams. How can you dream of peace when you are subjected to ongoing violence and terror and the other side has no desire to talk to you?

Yechezekel Landau’s words seem wildly unrealistic.

And yet, and yet… Isaac found a way of answering his rejected son, Esau’s, plea –“do you have a leftover blessing for me too” And look at the results.

Moses could not find a way of answering his half-brother, Pharaoh’s, plea: uveyrachtem gam oti – can you please bless me too? – and look at the results.

Let’s not stop dreaming of the impossible and lets not stop finding ways to bless even our adversaries, to see their humanity and to raise them up as our equals.

May that be our dream for Israel, for this country and for each other every day. May we learn to bless each other, and in so doing, find ourselves blessed as well. Amen.