As Rabbi Jack Riemer teaches, “to be modest in an ordinary time is difficult enough, but to be modest when you live in a society filled with so much arrogance is really difficult.”

Parshat Noah 2020

Rabbi Stephen Weiss

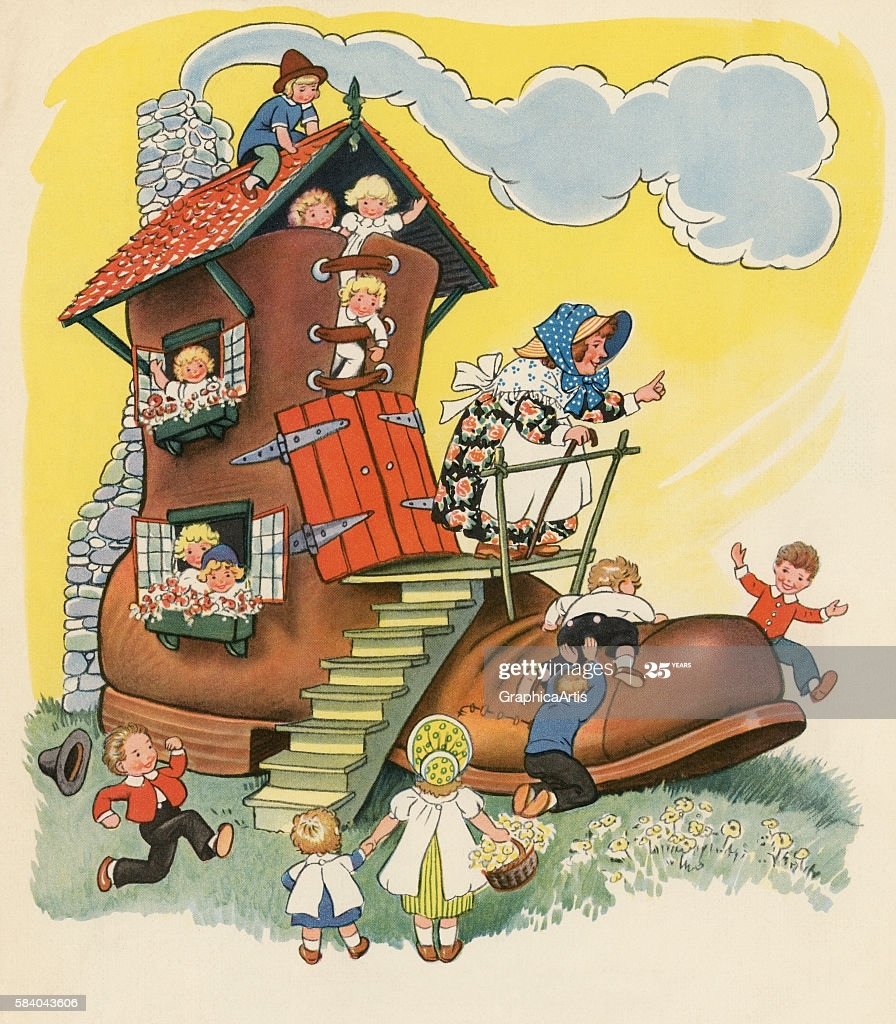

There was an old woman who lived in a shoe. She had so many children, she didn’t know what to do. You are all familiar with that mother goose rhyme. But exactly how many children did that old woman have?

Well, according to the Guinness Book of World Records, the record for the most prolific mother goes to the wife of Feodor Vassilyeva, a peasant from the town of Shuya, in Russia. Monastery records from the 1700’s indicate that Mrs. Vassilyeva gave birth to 69 children: Four sets of quadruplets, seven sets of triplets and sixteen sets of twins! Can you imagine?

What’s more, though the thought of going through pregnancy and labor that many times must is surely the more astonishing fact, we should note that those were all children of Feodor Vasilyeva’s first wife. His second wife gave birth to six sets of twins and two sets of triplets. That means Feodor is the father of 87 children! (of whom by the way, the record indicates all but two survived).

So, when we read the genealogy of Noah in this week’s parshah and are told that Yoktan, the grandson of Shem, had thirteen children, it is not surprising. Put into that context, it is not such a large number. Still, when we consider that the only other person with that many children in the whole Torah is Jacob, Yoktan’s prolificacy stands out.

What stands out even more is that the Torah gives us the name of every one of his children: “Yoktan begot Almodad, Shalef, Chazarmavet, Yarach, Hadoram, Uzal, Diklah, Oval, Avimael, Sh’va, Ofir, Chavilah and Yovav” (Genesis 10:26). These are names that are never mentioned again in the entire Bible. We are not told of their deeds nor are we informed about their descendants. We have no stories about them.

So, why does the Torah go to the trouble to tell us all thirteen names? The Torah is famously sparing in its use of vocabulary. It tells stories in the briefest possible way. Why then does the Torah take up the extra space in the scroll to tell us these thirteen names?

The great Torah commentator Rashi finds an answer in their father’s name. The root of the name Yoktan is ????? kuf tet nun – which spells ?????? katan – small. Yoktan, says Rashi – means “the one who makes himself small.” That is, the one who is humble and modest. It is because of Yoktan’s humility that he merits to be mentioned in the Torah along with his thirteen children.

One of the great Hassidic masters, Rabbi Avraham Chaim ben Gedalya of Zlatchov – known as the Zlatchover Rebbe, expands on Rashi’s comment. In his book, Ha-Orach L’Chaim, the Zlatchover Rebbe teaches that to understand the nature of Yoktan’s humility – and why it was so praiseworthy – you must consider him in the context of the times in which he lived.

Yoktan was born around the time of the generation of the Tower of Babel. This was a time marked by extraordinary arrogance. After all, this was the generation that sought to build that tower. They believed they could build a tower that would reach all the way into the heavens. They believed that if they could then climb that tower to the top, they could attack and defeat God and take God’s place. They believed that they could ultimately control the world and their destiny.

As Rabbi Jack Riemer teaches, “to be modest in an ordinary time is difficult enough, but to be modest when you live in a society filled with so much arrogance is really difficult.” That, says the Zlatchover, is Yoktan’s special merit.

What gave Yoktan the ability to maintain his humility living in an age of such hubris? To answer this, the Zlatchover zeros in on Yoktan’s thirteen children. Remember, the only other person with thirteen children in the whole Torah is Jacob. Why thirteen, and why include all their names and not just Yoktan’s name?

The Zlatchover teaches that Yoktan’s extraordinary humility came about because he sought to attach himself completely to the One True God.

How does the Zlatchover Rebbe know this? The Hebrew word for one is ?????? echad. Its letters are ????? alef, chet, dalet. Those letters have the numeric values of one, four and eight. Their sum – the sum of the word ?????? echad in gematria – is thirteen. Thirteen is also the number of Divine attributes that God reveals to Moses on Mount Sinai.

So, the names of the thirteen children are included to teach that Yoktan clung to ?????? Echad – the One True God. The thirteen children for the value thirteen in the word ?????? Echad, representing the One God. Yoktan tried to stay near to God, to stay loyal to God, to recognize that everything good in his life came from and belongs to God, to know that that every choice he makes, every thing he does, every use of his own talents and belongings, needed to be in the service of God. It was the presence of God in Yoktan’s life that gave him the strength to resist the trend in the society in which he lived and to maintain his extraordinary humility in a world of hubris.

The Zlatchover’s teaching has never been more important than it is today. After all, we are living in what might be called the new generation of Babel. We are capable of extraordinary accomplishments in science, medicine, engineering and more.

We literally build towers. Any skyscraper in America would dwarf the Biblical Tower of Babel. But it is not just our skyscrapers. We live in a time when we have gained extraordinary knowledge and the ability to manipulate our world. We have gotten used to the idea that we can make anything happen that we want.

Every day of our lives new discoveries and inventions enter the world, so much so that we almost take them for granted. We begin to see ourselves at the top of that tower, ready to take the place of God.

We no longer ask if anything is possible, only when. It is easy for us to reach the point at which we think that humanity is now capable of all the answers, that we have climbed the tower and replaced God. That hubris then spills over into other parts of our lives as we grow distant from our Creator and think in terms of what we have accomplished, our own greatness, and how we can individually fulfill our own desires. We shape our lives and our decisions by what we think, what we want, what we think we can do, without giving credit, without feeling in debt, without desiring to serve God. That is the danger of the generation of Babel.

Inevitably — like a tsunami sweeping over us that cannot be stopped — we experience the limits of our own abilities. We discover that the cars which unleashed our mobility and the industries that drive our economy are heating up our atmosphere, raising the possibility of an earth that will not be able to support life as we know it.

We find that the nuclear power plants that we build with what we thought were nearly infallible safeguards are not so safe. A real tsunami destroys a nuclear plant in Japan and radioactive materials wash up on the shore in San Francisco and Los Angeles.

A virus migrates from a bat to a wildcat and then to a human in a wet market. First one, then four then fifteen are infected. Suddenly the world is engulfed by pandemic. Lives are lost. Economies are stopped. Our everyday existenced is turned upside down.

Events like the spread of the coronavirus remind us we are not ultimately in control of our world. This pandemic has humbled us, reminding us to turn away from our selfish desires and to put others – and most importantly, to put God— before ourselves.

What is the answer to the hubris of our age? It is to follow in the footsteps of Yoktan. To seek to attach ourselves to ?????? Echad – the One God, to center our lives on God, to live in the service of God. It is to seek to emulate the thirteen attributes of God, to be compassionate and gracious, slow to anger, abounding in kindness and faithfulness to always be forgiving.

That is the challenge we face today: To seek, like Yoktan, to cling to the presence of God in our lives.