Rabbi Stephen Weiss

Rosh Hashanah 2015

it is precisely because no one better understands the plight of the stranger that God calls upon us to stand up for the stranger in our midst

At the tender age of three Eric Reich was deported, along with his family, from Germany to Poland. His entire family perished in Auschwitz. Only Eric survived. Eric was fortunate enough to be among the 10,000 children saved in the famous Kindertransport to Great Britain. He made aliyah at age 13 and lived on a Kibbutz. As a paratrooper in the Israel Defense Forces, he participated in the Sinai campaign. Later he returned to Britain, where he was knighted.

76 years later, Aylan Kurdi, also three years old, his 5 year old brother Ghallib and his mother, Rehan were not as fortunate. They, along with their father Abdullah, hailed from Kobani, a town on the Syrian border with Turkey, which saw heavy fighting and ISIS occupation. Abdullah had gotten his family across the border to Turkey and was hoping to ultimately come to Canada, where his sister lives.

They boarded a boat on the Turkish coast, hoping to reach the Greek Island of Kos, 2.5 miles away, slightly closer than the distance from here to Fairmount Circle. The boat sank. The life jackets did not work, only Abdullah survived.

Young Aylan’s body washed up on a Mediterranean beach, face down in the sand – wearing a soaked red shirt, cropped jeans and tiny Velcro sneakers.

The picture was so heartbreaking that it finally shook the world free of its shackles of apathy and self-interest. Like the shofar, it became a great alarm. It forced all of us around the globe to confront the dark reality of the refugee crisis and called out to us to answer our moral responsibility to act, to do our part to bring an end to the suffering.

And who understands that responsibility better than Sir Eric Arieh Reich, who now serves as chairman of the Association of Jewish Refugees’ Kindertransport Group. In a letter to Prime Minister Cameron, Lord Reich writes: “Without the intervention and determination of many people who are of many faiths, I – along with some 10,000 others – would have perished. I strongly believe that we must not stand by, while the oppressed need our help. We cannot ignore the sight of desperate people and in such a crisis we must act to save the most vulnerable refugees: the children, and provide them with the same sanctuary I, along with others, was fortunate to receive.”

And Lord Reich is not alone in this sentiment. Recently, a group of Jews from the Alyth Synagogue in London – all Holocaust child refugees, most from the Kindertransport – went to testify before the House of Parliament and urge that the UK accept a larger number of refugees.

While there, they also met with a group of young refugees from Syria. The Jewish refugees saw themselves in the young Syrians they met. One man from Hamburg, originally called Alex, talked about his parents writing to Brazil, to America, to Canada to get a visa and not being able to get one from anywhere, and that sense of desperation that he as a 7-year-old boy, which he was at the time, was so aware of until they were finally able to send him – only him — to England. His words call to mind stories such as the St Louis and the sins of the Evian Conference in which 32 nations, knowing the fate that awaited the Jews, shut their doors to them.

As Rabbi Mark Goldsmith of the Alyth synagogue told PRI: “If the government in the 1930s had listened to the critics who said we didn’t have room, and we had enough problems caring for our own, then the entire group stood before the Houses of Parliament with me would not have survived.”

We all know that the Kindertransport, as moving as the tale is, was the exception and not the rule. Our history is replete with examples of our people being marginalized, ostracized, persecuted, exiled, and shut out. That history dates back to our very founding as a people.

The Torah reminds us again and again: “You were slaves in the land of Egypt.” “Do not oppress the stranger for you were once strangers in a foreign land.” To be Jewish is to know what it means to be a stranger, to be a wanderer. To know what it means to live without hope and without allies willing to take you in.

And it is precisely because no one better understands the plight of the stranger that God calls upon us to stand up for the stranger in our midst, to shelter and defend them, to guarantee them safety, liberty, and equality.

That’s why I am so very proud that it is Jewish organizations that are leading the way when it comes to speaking out for these refugees and providing them assistance.

In the United Kingdom, World Jewish Relief – founded 70 years ago to carry out the Kindertransport – is now raising funds for Syrian refugees. The New North London Synagogue – a Masorti, Conservative synagogue – is operating a refugee drop in center that provides legal advice, medical treatment, counselling, meals and clothes. In Italy, Germany and elsewhere Jewish communities – often with the help of HIAS and the JDC — are providing shelter and programs to help refugees learn European languages, train for jobs and integrate into society.

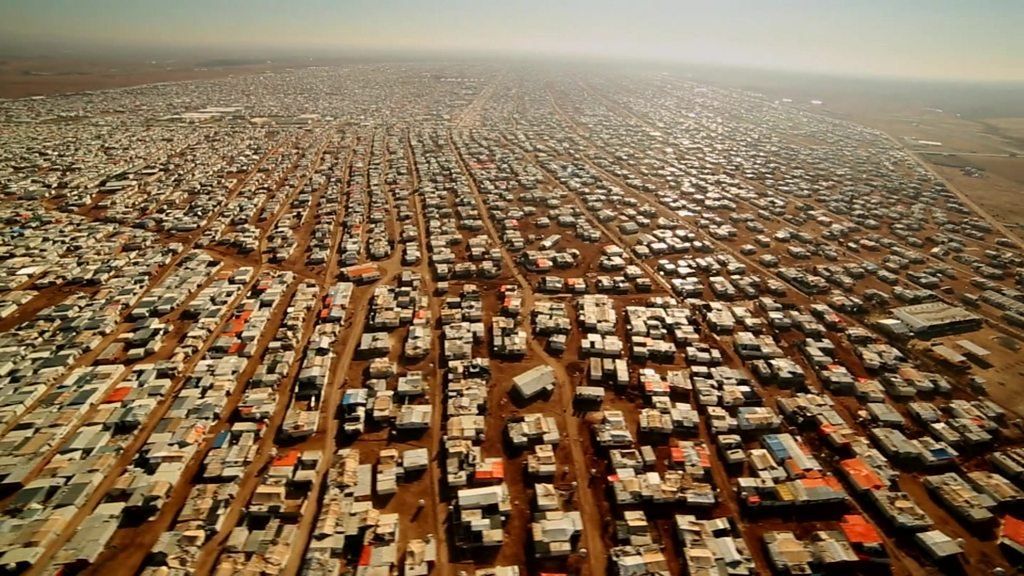

Even in Jordan, a Jewish presence can be felt. Za’atari is the second largest refugee camp in the world and the fourth largest population center in Jordan. There, the needs of the over 80,000 refugees – 85 percent of them women and children – are being met by two groups providing funds for clean water food, medical aid and advocacy. One, the Jewish Coalition for Syrian Refugees, is comprised of 50 Jewish organizations. The other, known as the Multi-Faith Alliance, formally involves partnerships and volunteers from all faiths. The overwhelming amount of money, staff and volunteers, however, are provided by Jewish donors and 24 Jewish organizations, including HIAS, the JDC, AJC, ADL, the JCPA, and the umbrella organizations of the three major Jewish movements (Reform, Conservative and Orthodox). Its director, Dr. Georgette Bennett was herself born in Budapest in 1946 to parents who were Holocaust survivors.

Israeli leaders have been debating whether or not Israel should open its door to refugees. Buji says yes. Bibi says no. It is true that Israel is a small country with limited resources. We can take pride that the Israel Defense forces have treated almost 2000 Syrians injured in fighting, and that Isra-AID – Israel’s equivalent of the Peace Corps — and the Israel Trauma Coalition are both on the ground working with refugees in Jordan. But it remains my hope that Israel will walk in the path laid out by Menachem Begin, who brought 66 Vietnamese Boat People to Israel, and will find a way to accommodate some number of Syrian refugees as well.

I understand the anxiety felt by those who would seek to close their eyes to the plight of Middle Eastern refugees.

Some point out that there are not enough countries in the Middle East doing enough to help their own. That may be true but that doesn’t change the fact that lives are at stake.

Some claim that if it were not for the Iraq war there would not be these refugees. Others claim that if we had not withdrawn there would not be these refugees. I say to you: It doesn’t matter. Leave that debate alone. It doesn’t matter whether you thought the Iraq war was good or bad, withdrawing was good or bad. There are millions of people’s lives at stake now. That’s what matters. What will we do to save those lives?

Some claim that many of these refugees are not fleeing for safety but merely seeking a better standard of living. Others fear those who are different in language, appearance, faith and customs. Some are concerned that terrorists and jihadists will slip into the West among the teeming refugees. Some worry that refugees will blame the West for their problems and turn against us. Still others point out that many of these refugees – such as those from Syria – come from countries that have bred intense hatred for Israel and Jews.

I want to share with you two responses to those concerns. The first is that we would do well to remember that these same refrains were raised at the Evian Conference as excuses to not help Jews. Yes, these refugees come from countries hostile to Jews. But that does not mean that all its citizens are themselves our enemies.

Let me share with you a very powerful and stirring Midrash on this morning’s Torah reading. The Torah tells us that Abraham sends Hagar and Ishmael into the wilderness. God hears the voice of the lad ba-asher hu sham – where he is, and God provides a well of water to slake his thirst. God saves Ishmael, and generations of commentators are left to struggle with this question: How could God save Ishmael, whose descendants, the Arab people, who would cause the Jewish people such grief?

The answer is found in Midrash Tanhuma which draws our attention to the seemingly superfluous phrase ba-asher hu sham – where he is, which it explains with the following legend:

When Ishmael was dying in the wilderness, and God was about to save him, the ministering angels object. “Master of the universe,” they protested, “What are you doing? If you save this lad today, then his descendants will one day kill your chosen people, the children of Isaac! Let Ishmael die now, to prevent what his offspring will one day do to a people you love.”

God responds: “What is Ishmael right now? Righteous or wicked?” And the angels are forced to admit: “At this moment he is only a lad, and he is righteous.” God then tells the angels: “According to his present deeds will I judge him.”

God says of Ishmael: “I will judge him ba-asher hu sham – where he is now – that is, in his present state, not according to what he or his descendants might do in some time in the future.”

And so we must say of the current refugees. We cannot know what the impact of Muslim migration will be on Europe, on the already tenuous future of Europe’s Jewish communities, on the EU’s relationship with Israel. We cannot know whether a refugee child will grow up to be good or bad, filed with love or hate. All we can do is answer the cry of the oppressed ba-asher hu sham – where they are now. We must see them as they are now: as fathers, mothers, children trying to survive, seeking to escape the ravages of terror, oppression and war.

My second response to concerns over helping Middle East refugees is that our reaching out and helping Arab refugees presents us with a unique opportunity to build bridges of understanding and appreciation, of friendship, that can help change Arab attitudes toward Jews and Israel.

That approach is nothing new and nothing controversial. It is one of the reasons Israel is first on the scene at times of disaster not only in friendly countries but also in hostile ones such as Indonesia. It is also one of the reasons Israel has been providing medical and agricultural assistance to third world countries for decades. Here too the same principle holds: kindness breeds friendship. Jews in Italy, Germany and even Jordan have shared their encounters with refugees who are learning for the first time through them about the Holocaust, who express their gratitude to their Jewish friends and their astonishment that Jews and Muslims could have such good relationships.

In Milan, Italy, the Jewish community is hosting a refugee shelter inside the Holocaust Memorial which is on Platform 21, the infamous train station from which Jews were deported. Every refugee who enters learns their story, and it changes the way they look at Jews and Israel forever. In Germany, my colleague at the Masorti synagogue tells me that, after hosting a Hanukkah party to which Muslim refugees were invited, a Muslim woman said to her “Tell me, this relationship between Jews and Muslims, is this normal in Germany?” “Yes,” the rabbi said, and the Muslim woman learned something in that moment. These are the seeds of change.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, former chief Rabbi of Britain, writes: “I used to think that the most important line in the Bible was ‘Love your neighbour as yourself’. Then I realised that it is easy to love your neighbour because he or she is usually quite like yourself. What is hard is to love the stranger, one whose colour, culture or creed is different from yours. That is why the command, ‘Love the stranger because you were once strangers’, resonates so often throughout the Bible.” Rabbi Sacks concludes: “It is summoning us now.”

So what can we do?

First, Let your voice be head to urge this country and others to make formal plans to take in larger numbers of Middle Eastern and African refugees, to give them hope and a home. This country was built by immigrants. Our families were those immigrants, who arrived on these shores not always fleeing from the horrors of the Holocaust, but sometimes fleeing from lesser but still terrible horrors, from persecution under the Czar, from “eternal” drafts from which Jews were never released by the Poles, from hunger, from pogrom… they came here seeking freedom and opportunity. Raise your voices. Let us give these refugees freedom and opportunity.

Second, you can contribute to organizations and agencies providing refugee relief. There are many of them. If you google HIAS, you will find on their website several of those organizations listed as well as HIAS itself. Again I remind you ADL, AJC, JCPA and many other of our umbrella organizations are deeply involved, and you can contribute through the Conservative movement, or just find a refugee agency online and help.

Finally, I am exploring ways – along with Rabbi Rudin Luria, who is also speaking on this topic this morning – in which our synagogue can partner with a synagogue in Europe to be more directly involved, to help in a hands on way those seeking refuge. I hope that as you hear about those efforts unfolding, you will join with me. Over the course of the year I hope that we will look for other more sustained ways in which we can play a role.

Let me close by once more quoting Rabbi Jonathan Sacks. He writes: “A strong humanitarian response on the part of Europe and the international community could achieve what military intervention and political negotiation have failed to achieve. This would constitute the clearest evidence that the European experience of two world wars and the Holocaust have taught that free societies, where people of all faiths and ethnicities make space for one another, are the only way to honour our shared humanity, whether we conceive that humanity in secular or religious terms. Fail this and we will have failed one of the fundamental tests of humanity.”

I would add: It is one of our most fundamental tests as Jews as well. May we rise up to that test, and demonstrate our commitment to remember the stranger.

Shanah tovah.