Shabbat Shemini/Yom Ha-Shoah

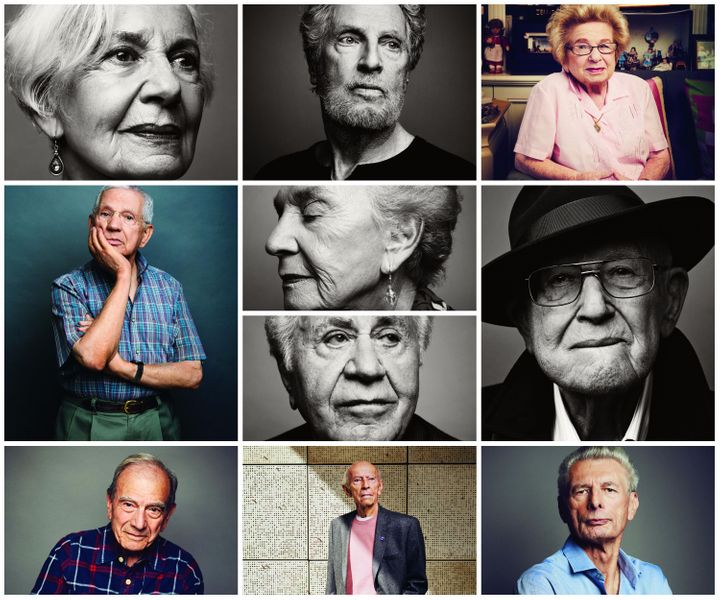

Covid-19 is stripping our world of some of its most important voices, those who courageously re-live the horrors they endured in the Shoah by re-telling their stories out of a deeply felt drive to ensure that such atrocities never happen again.

If Margit Buchhalter Feldman had not lied about her age to the Nazis, the 15-year-old would have been murdered with her family at Auschwitz.

Margit was an only child, born in Budapest on June 12, 1929, the same birth date as Anne Frank. In 1944, Feldman and her family were taken from their home in the small agricultural town of Tolcsva, near the Czech border, and imprisoned in a nearby ghetto before heading to Auschwitz. She knew that as a child. she would be sent straight to the gas chamber, as were her parents. She lied and told them she was 18 and was sent instead to the work camp. Later she was transferred to a number of concentration camps, before ending up in Bergen-Belsen. In the 2016 documentary titled after the number tattooed on her arm, “Not A23039” Margit remembered being surrounded by death. She said she could still taste the horrible soup that was served — often with worms swimming around the bowl. “You were put into a barrack, where people died,” she recalled in the documentary. “The straw that you laid down was full of whatever came out of their bodies — vomit or discretion. It didn’t take 24 hours for your body to get covered with lice.”

Margit was liberated from Bergen-Belsen by the British on April 15, 1945. The seventh day of Pesach this year, April 15, just 3 days ago was the 75th anniversary of Margit’s liberation. Only 16 years old, Margit was the sole member of her extended family to survive. When the British soldiers found her, she was suffering from pneumonia and pleurisy, and had been injured by an explosive set by the Germans who were trying to destroy the camp.

It took Margit decades before she was able to open up. Once she did, she devoted her life to telling her inspiring story. She touched the hearts of thousands of students, educators, and members of her central New Jersey community. She also worked with the governor of New Jersey to establish a Holocaust Education Commission and she helped pass a bill that mandated a Holocaust and genocide curriculum in New Jersey public schools. She tells her story in a very moving book which is entitled: Margit: A Teenager’s Journey Through the Holocaust and Beyond. Her goal, she said, was to inspire people to stand up for one another and fight against all forms of prejudice and hate.

Margit survived the horrors of Nazi Germany, but on this past April 14th, just one day before the 75th anniversary of her liberation, Covid-19 took her life. Her husband, Harvey, remains in the hospital with the coronavirus, struggling for his life.

I have often said that in 25 years, it is likely that there will no longer be Holocaust survivors who are able to provide firsthand testimony to the dark truths of the Holocaust. But that timetable has been fast-tracked by the coronavirus pandemic. Covid-19 is stripping our world of some of its most important voices, those who courageously re-live the horrors they endured in the Shoah by re-telling their stories out of a deeply felt drive to ensure that such atrocities never happen again. What will happen when they are gone?

When the last survivor will leave this world, there will be no more people able to say, “I’ve been there.” No more testimonies. There will be no one to show the tattoo on their arm, no one to stand up and contradict the Holocaust revisionists, deniers who claim the Holocaust is a contrivance of the Jewish imagination used to blackmail the world into supporting Israel.

Its not just the survivors who are disappearing. The physical infrastructure of the Nazi camps deteriorates day by day. Barbed wire fences are stolen so the wire can be sold on the black market. Wooden barracks are weathering away. Rebuilding them doesn’t help. I recall our synagogue trip to Poland in 2002. Our guide – a holocaust professor from Oxford University – explained to us that the organization that now runs Auschwitz as a museum sought to restore the camp so that in the future people would see the camp as it was under the Nazi regime. David Irving – the famous Holocaust Denier who later sued professor Deborah Lipstadt for libel and lost – showed up at Auschwitz with a film crew. He filmed the workers restoring barbed wire and repairing damaged barracks and he added narration stating, “see how they are building this fictitious camp as a film set to propagate Jewish lies.”

Of course, one can always open a history book, but for most people, their greatest exposure to the Holocaust will come through the movies. The problem us that Hollywood’s representation of the Holocaust often ends up doing its own type of damage to historic memory. Take the recent film Jo Jo Rabbit as an example. It portrays a German boy saving a Jewish girl with the silent help of a Nazi officer. If you get your history from the popular media, you would think that the majority of Germans opposed the final solution.

What will we do when the survivors are gone?

In the first half of 2019 there were over 800 anti-Semitic incidents in the US alone, including the attack on the synagogue in Poway. The second half of the year was not any better. In December 2019 three people were shot down in cold blood in a Kosher market in New jersey and Jewish celebrants were attacked with a machete in a rabbi’s home in Monsey on the festival of Hannukah. All this only 14 months after the deadly massacre at Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh. At the same time, France had a 74% increase in anti-Semitic incidents, while in Germany attacks on Jews increased by 60%

But even more disturbing, a recent poll showed that while 89% of European Jews felt that anti-Semitism had significantly increased over the past five years, only 36% of the general population felt that it had. 36%.

What will we do when the survivors are gone?

In this week’s Torah portion, we read about the death of Aaron’s sons, Nadav and Avihu. The two brought what the Torah describes as a strange fire to the altar of the Tabernacle. Fire came down from heaven and consumed them. When he learns of his son’s death, the Torah says, vayidom Aharon – Aaron is silent. Some commentators suggest that Aaron’s silence is an expression of the depth of his grief; but I want to suggest a different way of reading this text. It may be that with these two words, the Torah is castigating Aaron for his failure in an important moment. Perhaps in fact Nadav and Avihu did not deserve to die. Perhaps Aaron should have stood up and protested their unjust death.

The word vayidom, which means that he was silent, contains within it the word dam: blood. Perhaps the meaning here is that in Aaron’s silence, he had his sons’ blood on his hands. By not speaking out in protest over their deaths, Aaron becomes as it were retroactively complicit.

The Talmud offers an imaginary scenario in which Balaam, Job and Jethro served as advisors to Pharaoh. Balaam – whom the Moabite king Balak would later hire to curse the Israelites – counseled Pharaoh to enslave the Jews and was punished with a violent death. Jethro – the Midianite priest who would later become Moses’ father-in-law – opposed Pharaoh’s decrees but was forced to flee. He was rewarded in that his descendants became great Torah scholars. Job – who has his own book in the Bible – remained neutral and was punished with horrible suffering.

What did Job do wrong? Rabbi Chaim Shmuelevitz taught that Job’s sin was he stayed silent. We cannot sit back and treat evil as something which is just an ordinary part of this world. In the face of evil, we must scream out.

As the number of survivors who can tell their story dwindles, it becomes the obligation of each and every one of us to speak out – to scream out – and tell the truth of the Holocaust. Not in generalities, but in details.

If you have survivors in your family, make sure you know their stories. If you do not have survivors in your own family, find stories of survivors and make them your own. Either way, memorize them. Internalize them. Share them with the world. Because you and I – very soon we will be the only ones left to testify.

Rabbi Romi Cohen was born in Pressberg, Czechoslovakia in 1929. When the Nazis invaded Hungary intent on murdering the Jews, he was only ten years old. His family escaped into Hungary where he studied at the esteemed Puppa Yeshiva. But very soon the Nazis took over Hungary too. Young Romi returned home to Czechoslovakia, this time carrying forged Christian identification papers. Romi – then 16 years old — became an informal member of the underground and used his connections to help find housing for Jewish refugees and to supply them with false Christian papers. He saved 56 Jewish families. The identity papers he made were very realistic. He had a connection to someone working at Gestapo headquarters who supplied him with German seals to stamp the documents.

Eventually Romi was arrested on suspicion of carrying false documents. After a daring escape, he decided to join the partisans hiding in the mountains. To reach the mountains, Romi forged a German military travel order, sending himself to the last German outpost before partisan-controlled territory.

“[The Germans] all shook my hand and wished me luck,” he later recalled. “They thought I was going to go strike a blow for the Reich.” By the time he joined the partisans, the Germans were already in retreat. His brigade drove them back westward, while capturing, interrogating, and executing SS officers. When Hungary was liberated, Romi returned to Czechoslovakia.

After the war, Romi came to the United States. He became a great Jewish scholar and a mohel who performed thousands of brises. He also financed the education of 70 rabbinical students in Israel. He viewed these rabbis as his own grandchildren.

Rabbi Romi Cohen died on Tuesday March 24 of complications from the coronavirus.

Everyone is familiar with the moving poem, “The Last Butterfly” which was found written on the wall in Theresienstadt. A number of years ago, a somewhat different poem was read at a UN commemoration of the Holocaust:

“I am the last one left, I remained a human being even when I was just a number;

a loaf of bread is something that you eat, but under the pillow it I would always keep.

…………I am like the burning bush;

you will remain here to tell the story.

I am the last one left, still attached to the Israelites in the desert;

I have no rest, I wander and roam;

all that remains are the memories from the Cattle cars.

I am the last one left…..

I call out to you…….

you will remain here to tell the story

there are millions of eyes staring at me now, How can I give up?

I am the last one left, to tell the story.”

You and I — it is incumbent upon us now to tell the story. Be sure to light your yellow candle to mark Yom Ha-Shoah. If you do not have one, we will be sending out a link to a virtual yellow candle on the web. And be sure to join the community for its virtual Yom HaShoah commemoration this week. And make it a point this week to learn the stories of some of the survivors. Memorize them. Tell them. One day there will be no one to tell the story except you.